“Hector the Hero” has become a popular fiddle tune in slow 6/8. Some play it in a more upbeat way, as a waltz, but after learning the history of the tune, I find it difficult to play in any other way than as a lament.

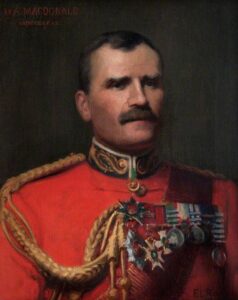

On March 25, 1903, one of the heroes of Victorian Scotland, Hector Macdonald, known as “Fighting Mac,” returned to his room from breakfast at a Paris hotel and shot himself. Two days later, the great fiddler and composer James Scott Skinner wrote one of his most famous and moving tunes, “Hector the Hero.”

Raised in a small town near Dingwall, north of Inverness, Major-General Sir Hector Macdonald had risen quickly through the ranks of the British army, distinguishing himself with feats of daring, discipline and leadership in Afghanistan, Egypt, Sudan, India and South Africa. There were those who  dubbed him the greatest Scottish soldier since William Wallace. Macdonald had been appointed aide-de-camp to both Queen Victoria and King Edward VII, and was feted throughout the UK, though his humble origins did not prepare him for the gushing plaudits of society. His high position in the army was made possible by the Cardwell Reforms of 1871, which allowed for promotion based on merit, and abolished the purchase of commissions in the army by well-off seekers of glory who were not always the most qualified of military leaders.

dubbed him the greatest Scottish soldier since William Wallace. Macdonald had been appointed aide-de-camp to both Queen Victoria and King Edward VII, and was feted throughout the UK, though his humble origins did not prepare him for the gushing plaudits of society. His high position in the army was made possible by the Cardwell Reforms of 1871, which allowed for promotion based on merit, and abolished the purchase of commissions in the army by well-off seekers of glory who were not always the most qualified of military leaders.

That morning at the Paris hotel, Macdonald was startled to see his photo in the international edition of the New York Herald, accompanied by a story about “grave accusations” of “immorality” against him. Continue reading Hector the Hero